Stories lose their meaning once the heroes move on.

Five, or four and a half, brothers from Orkney serve as knights to Arthur. Gawain is most famous, then the half, Medraut, teased by the elder sons as ‘Mouse’, and Agrivaine and Gareth. Less renowned, and he prefers it that way, is Gaheris.

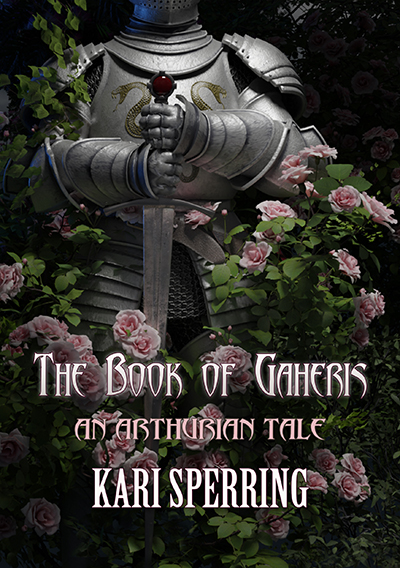

Kari Sperring, as she notes in her afterword to this lovely new Newcon Press volume, loves the underdog. So, of course, she chooses to write his story. The Book of Gaheris comprises two previously published novellas (Serpent Rose, 2019 and Rose Knot from 2021) and two new slightly shorter tales.

Arthur and his court have been explored so many times, of course. With works that might best be described as purely Malory fan fic common. No judgement on fan fic implied but it is clear that certain works are entirely taken from this one source. And there are the Tourist Fantasies, based not on Malory or Geoffrey of Monmouth or Chretien de Troyes etc, but on that shallow, tourist guide, perceived Arthur absorbed by osmosis from films and TV rather than research.

Kari Sperring is not one of those writers. As a medieval historian she has read her sources, and the alternative sources, and more. She understands her material. This gives her stories a veracity and depth I enjoyed immensely. It also gives her the background knowledge that these stories are far from immutable, characters are not sacrosanct, and she can mould them.

One of the things I find important in historical fiction is not pedantic accuracy. It is that major changes must serve a purpose, and should flow with the factual. The dialogue between characters is invented but that creates the characters which in turn shapes the voices in that dialogue. Here, as far as I can tell, changes are seamless. Oh the names are tweaked, Lionis here is other versions Lyoness, Marcus is Mark and the famous Sir Gawain is Gavin to his friends and brothers (who aren’t the same thing.) Nothing else is obvious beyond the needs of modern fiction storying.

It is in storing the well-known or slightly known at least, that Sperring succeeds. Her characters feud, and play, and love with such wit that a sense of family dynamics is built. This is near invisible world building.

Kari Sperring is not a comic writer in the sense of writing for laughs, but there are frequent asides, moments of warm banter, ironic touches that raise laughter throughout these stories and which deceive the reader from what we ought to recall: the essential tragedy of these legends. And thus the deaths, when they come, are more brutal and heartbreaking. I shed a tear at the last of these, such is the way these foolish, arrogant, violent, emotionally clumsy men have ingrained themselves.

The Book of Gaheris is the title, yet, in fitting with his preference for the background, Gaheris is not the overt focus of any of these stories. We begin, in Serpent Rose, quite deliberately with Lamorak de Galis the younger knight besotted with Gaheris despite family history condemning this to disaster. It is Lamorak who utilises agency that forces the novella’s dramatic climax, and only then does Gaheris act.

In Rose Knot it is the women, the Orkney wives, Luned and Lionis, and bored, careless Essylt who gossip, scheme and find consequences beyond their anticipation and wit to resolve. A chastity test for the men reveals unanticipated secrets. Including whose faithfulness is as disturbing as his fellows disloyalty. Gaheris now is less sympathetic from their viewpoint. Broken pieces are only partially restored.

Knotted Thorn, the third story, is more magical. Set across two timelines, “Now” and “Then” it is the story of Thorn of the White Lands, alone in her ruined castle until a mysterious visitor reminds her of past tragedy. “Then” is told in high romantic epic style which is at odds with the more straightforward telling of “Now” but appropriately so, as it tells of a supposed hero and his squire encountering enchantment and, years later a return in penance. It’s a story which seems to hesitate at the point of instauration. Stories lose their meaning once the heroes move on. (p.165) And when they return?

Gawain it is who tells the final piece, Thorned Serpent where we also see a more complex Medraut, and perhaps a redeemed Safere, the closest friend of betrayed Lamorak. On the one hand this is the mystery of the suspected murder of the Queen’s maid and Agrivaine’s innocent wife Laurel. Already the bitterest of the Orkneys, he is driven to rage and seeming madness. It is a classic depiction of the guilt-tinged stage of grief, but in the shocking, violent outcome there is worse to come for reader and for Orkney. As I said, tears were shed. The sons of Lot and Margawse, once divided by desire for peace and for vengeance, came together roughly, only to be torn apart again by the lingering, generational consequences of half told histories.

The Book of Gaheris is light, in places, full of the glamour (in its magical sense,) of court. It charms the reader with Lamorak’s puppy-like persistence, Kay’s bluntness, the humorously contrasting brothers and their equally contrasting mismatched wives, the passing jibes at other knights such as dull Sir Bors, the mysterious Safere and the largely offstage presences of Lancelot, Guenever and Arthur. It relaxes us with casual, demotic names, Heris, Gavin, Gari, Agri and, though he objects mildly, Mouse. But barely beneath this is a serious note; grudges are held, not over who actually killed Lot or Pellinore but who is suspected. Blame, and vows of revenge, is apportioned on suspicion and assumption. The consequences, repeatedly, in all four stories are disastrous. Here lies meaning after the hero is gone.

Read individually, each novella is an interesting, enjoyable read. Individually Gaheris is present but, as is his wont, not centred. As a collection though, as Gawain says Gaheris was always there. It sounds foolish, stated so badly. But it’s the truth. (p.207) The diffident hero. In that way The Book of Gaheris is a tribute to Gaheris, acknowledging that the most obvious, most visible, loudest, is not the most significant. Stories lose their meaning once the heroes move on. But the hero is not always who you think.